Showing posts with label Sitte. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Sitte. Show all posts

Sunday, 3 November 2013

Camillo Sitte: City Planning according to Artistic Principles 1889

A précis by Reece Singleton

Camillo Sitte’s 124 year old text, 'Der Städtebau nach seinen künstlerischen Grundsätzen' is his most famous and respected critique on 19th century urban aesthetic and city planning. It was arguably ahead of its time as the majority of its arguments are still being widely and fiercely debated today. His main concerns are that of public space (the Plaza) and the interaction of the built fabric of the city within its setting. He describes buildings as oil paintings that must have a good frame to work as a whole. He goes on to criticize contemporary planning technique as ‘unartistic’ and defines the approach to modern planning is seen as a ‘technical problem’. He ultimately tries to redress the lack of artistic flair through his theoretical solutions to public space.

Sitte’s background as Architect and Academic informed his thoughts and theories of how city planning should occur. He frequently brings the focus of the text back to antiquity and looks at how the ancient civilizations managed their public space, going on to say that they were able to marry art with function in a way that was quickly being forgotten in modern city planning. His examples of ancient Rome and Greece describe the essence of the city as Sitte saw it and how space, particularly plazas, could be an overwhelming myriad of experiences from the ephemeral transient journey to the protracted and truly spiritual revelation. He emphasizes how the ancient populations developed their cities in a way that was dominated by open space. Homes were designed around courtyards and public plazas where therefore to be looked upon as open, yet contained public rooms. These plazas therefore, were a space of practical and vital functional use, so the space was integrated into surroundings buildings, creating a rapport between the square and public buildings.

Sitte cites this integration of Plaza and Buildings as a key feature of antiquity that makes squares in the ancient cities of Rome, Pisa and Athens feel comfortable.

Sitte speaks of ancient city squares and plans with great passion and fervor but laments that, in the nineteenth century, we have lost through modern planning techniques the ability to create spaces that feel right, in both scale and decoration. He speaks about the new order of modern public space, its uniform regularity such as the ‘gridiron’ urban form developed in Mannheim and its lack of containment. He says that the modern city plan is thought of too much in plan and little thought is given over to the vertical proportions. Sitte sees the modern square as excessively large and out of proportion to the buildings it is surrounded by. He sees that the regularity of Urban form as ‘boring’ and unappealing to the visitor of the square and that, modern buildings of the era were being used as the basis of public space and that little consideration is given to the public space and overall outcome. He argues that more emphasis is given to the function of public space as a means to lay out a city plan than the overall form which in turn can influence function. He stands against the popular principle of symmetry and geometric design, going on to explain the original principle of symmetry is more aligned to proportion than a mirror image. He speaks against boulevards, street and square widening as embracing isolation and providing too much with which the eye could contend. This is contrasted with the irregularity of the ancient square and how they were considered as a whole with the buildings that encased them and the monuments and artistic flourishes that are equally important, developing the overall form and beauty of the space.

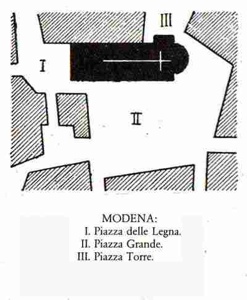

Sitte travels across Europe referencing differing examples of the plaza from Germany, Austria and Italy. Using these key examples he develops a way of understanding the squares of the ancient times and perception of its proportions between monuments and surrounding urban fabric. He argues that there is too much of a trend for isolation with monuments, stating the example that the modern Church is typically placed in isolation in a square, and that consequently rather than making a square, a wide street is created that round the entire distance of the Church. He argues that monuments should not be given over to the geometric centre of public space but should be placed around the edges of the space to provide a backdrop and interest.

He describes modern planning as being to restrictive and obsessed with issues of the day such as hygiene and transport. He goes on to say that by making the city healthier and more hygienic, something that he calls a noble aim and success story, we have created a sterility in the art and design of the city. He suggests that some artistic flourishes would no longer be allowed, such as a sweeping external staircase, for fear of health and safety in icy weather, and deplores the fact that some of these ancient design features will be internalized and lost from the public realm. Sitte again describes his despair at planning becoming a technical exercise, confined to the drawing board of municipalities, with little aspect of competition and creativity, accepting that in these fields pragmatism can come before the picturesque.

In the end of the book, Sitte tables ideas of how to improve the plaza and public space. Using the example of Vienna, his home city, he develops pragmatic solutions to some urban planning issues. He explains how street layouts can affect traffic flow and how best to counteract this, how to ensure the city does not become a monotonous block and emphasizes the importance of views and experience in the decoration and organization of public city space. He goes on to lay a foundation for planners, saying that the detail is not for them, that planning should concern only the streets and city at large and the rest be left to private design.

Although Sitte argues for the use of planning techniques of the ancients, he doesn’t appeal for historical replication of what has gone before. He argues that Urbanism calls for solutions of the day, but that by applying well worn and justifiable principles of years gone by we can create better space for our Cities. His works have influenced generations of Urbanists and Planners, and after falling out of favour, became the inspiration of some of those involved with the Townscape movement. Sitte’s argument for better city planning by embracing the intrinsic artistic nature of humans is a noble one and has led to the development of beautiful cities. Whether we have learned any lessons from his writings and continue to develop in a way he set out is still to be seen.

Wednesday, 21 November 2012

Camillo Sitte: City Planning According to Artistic Principles (1889)

Reviewed by Thomas Sydney

Despite being written over 120 years ago, Camillo Sitte’s most famous work is still seen as relevant today as it was when published in 1889. City Planning according to Artistic Principles is not purely an attack on the modern planning systems of the time, but an attempt to define a unity between modern and artistic methods through the creation of suitable public space. Upon its publication a new breed of theorists and practitioners developed who were concerned with the city and its planning.

Camillo Sitte was born in Vienna and it was here where he conducted the basis of his work. Whilst Sitte trained as an Architect, he had a strong artistic background and found prominence as an academic. He worked in a time of intense change in European cities as economic factors, sanitation and transport were becoming the most important influences on city planning - planning was becoming an exercise undertaken in plan on the drafting board, not on site in the street or the square.

He travelled extensively throughout Europe visiting cities in Italy, France and Germany as well as his native Austria. Through his travels, Sitte observed how these cities had developed and established a set of principles by which he believed cities should be planned. These ideas were based primarily on the plaza and associated public space and were presented in City Planning according to Artistic Principles. The book is mainly concerned with the increasingly technical way our cities were being designed at the expense of traditional artistic methods. Whilst Sitte laments the loss of these artistic methods and techniques witnessed during his frequent travels throughout Europe, he accepted that modern techniques were required in city planning with particular regard to increased levels of hygiene and motorised traffic.

Sitte was concerned that impressive modern buildings were increasingly being seen against a backdrop of poor public space as all resources were poured into the architecture of a building, not its surroundings. From his travels, he saw the work of the Renaissance and Baroque periods as exemplar in their use and manipulation of public space and as such he wanted to achieve a unity between modern methods and the artistic techniques of the past.

City Planning according to Artistic Principles maintains that the key element of successful city planning is the plaza or public square. There exists a context and history of use in these public spaces which make them vital to cities. When created and utilised correctly they create a backdrop to everyday life within the city, animating their surrounding buildings as well as providing a space to observe powerful buildings and monuments as they were intended to be seen.

Sitte observed many plazas during his travels and defined three types of public plaza based upon their intended use; the palace plaza, the cathedral plaza and the town hall plaza. These public spaces concentrated all the prominent buildings of their type in one pure space within the city where all distraction and unnecessary elements could be excluded. Sitte cites the Palazzo Del Duomo in Pisa as an exemplar religious plaza where the placement of the cathedral, baptistry, crypt and religious quarters within one unified space creates a ‘pure chord’ rarely seen in today’s cities.

One of the key characteristics of successful public plazas is their enclosed nature, restricting views out of the space and limiting endless perspectives. Aligned with this idea is that of buildings being built into the walls of the plaza. Sitte states that the centre of plazas are not suitable positions for buildings, the best location being tied in to the plaza walls to ensure the enclosure of the public space. He backs this stance up with his observations of churches in Rome where only 6 of the 255 churches are not attached to another building.

Sitte is also concerned with the position of monuments within public spaces. As with the siting of buildings, he believes that the centres of plazas should be kept free to allow essential lines of communication and sight to be maintained. He observes that modern plazas are often blocked by the installation of a statue on the central axis. A more suitable approach is the placement of items around the edge of a plaza which allows for more decorations as well as developing more dramatic environments for statues. The history of Michelangelo’s David is cited as an example of how modern thought has spoilt the appreciation of the famous statue. Michelangelo created the marble statue to sit in front of the Palazzo Vecchio in the Palazzo della Signoria in Florence. Its position here contrasted with the surroundings, emphasising the scale of the work; upon its relocation within an art gallery after over 350 years this contrast was lost.

Through all this, Sitte’s main concern is that of space. He states that the plaza should define an area of suitable proportions that people could comprehend and understand the extent of the space. Sitte mentions that the increasingly large proportions of modern plazas is linked to the newly diagnosed condition of agoraphobia.

City Planning according to Artistic Principles is also concerned about the increasing use of grid layouts for streets in the development of cities. Sitte uses similar principles to those of plazas to define how streets should work within the city; notably the definition of suitable space, the reduction of endless perspectives and the bending or re-routing of streets to avoid the creation of awkward junctions and plazas.

Camillo Sitte accepts that modern systems of city planning cannot be avoided and can be of benefit if developed with artistic methods in mind. He draws attention to several examples of modern development from Germany and Austria which he sees as more suitable as well as highlighting several of his own exemplar projects which try to unite artistic methods into a modern city planning system.

He concludes by presenting a series of proposals for Vienna’s Western Ringstrasse where he suggests several interventions to adapt the current city layout to create more suitable public spaces for the existing prominent and powerful buildings.

These proposals ultimately fell on deaf ears as none were implemented. However, the ideas put forward by Camillo Sitte in City Planning according to Artistic Principles have persisted and found favour particularily with the Townscape movement of the 1950s.

Tuesday, 29 November 2011

Camillo Sitte: City Building According To Artistic Principles (1889)

Reviewed by Jack Penford Baker

INTRODUCTION

Written in 1889, Camillo Sitte’s book City Building According to Artistic Principles, is seen as the first publication to discuss the concept of Urban Planning. Cited still to this day, his critical analysis of the then modern planning principles and historical precedents paved the way for a new breed of theoretical practitioners in the art of Urbanism.

The book informally breaks down into three apparent sections. Initially Sitte outlines and documents what he perceives to be worthwhile paradigms of historical public spaces. Next he looks to the present, and systematically reveals the failures of the then modern city planning principals before finally outlining a set of solutions, presented in the form of a case study of Vienna’s own plazas, compiling the first significant documentation on what is now a global practice; Urbanism.

_PAST

The early parts of the book look towards the analysis of Sitte’s depiction of successful urban space. Through decades of travelling across Italy, Germany and other central European countries he discovered what he understood to be the epitome of city planning. Italian cities with Roman and Medieval influences portrayed Sittes’s ideology, an ideology that looked at the personal experience of individuals within the spaces of the city, not of the city as a machine. To him Roman spaces worked and still work, and it is with the past’s understanding of urban space that is fundamental in the understanding of the problem with modern city planning.

Piazza Della Signoria in Firenze, Italy, displays a crucial element of piazza design. Within the square Michelangelo created the infamous statue of David, originally planned to sit upon the cathedral, Michelangelo argued for it to be positioned in the square. Instead of positioning it in the centre for all to experience, Michelangelo insisted for it to sit adjacent to the palazzo entrance. A somewhat odd request, however the choice resembled an element of town planning that Sitte believes is crucial in modern times. By sitting the statue away from the central axis it removes any interference with circulation, and views to the entrances and buildings. The concept is taken further with the principle addressed to the positioning of churches. As an Englishman, one would always assume that churches be isolated and monumental in their context. However Sitte believes that churches within a square should sit not in isolation, rather on the contrary, as part of the perimeter. By referencing Rome he outlines how some 6 out of 255 churches sit on their own, a striking difference. “That the center of plazas be kept free”.

He further progresses to outline other key principles of ancient urban spaces that he believes have been lost in modern planning. With his reiterated reinforcing of the pedestrians experience as the true factor of success, Sitte states how the design of streets in successful precedents always revolves around that of the experience. Their designs follow key formulas, for example he believes that all entrances views into a plaza should not infringe on each other, and should enter from an obscure angle. Other such rules relate to the dimensions of the space, for example the squares width must be greater than that of the focal building’s height, but not be anymore than twice its size in order to create a welcoming space.

Upon all of the guidelines that Sitte mentions through the use of precedents, he emphasises the natural growth of such squares, and the passing of time as a fundamental key to generating the ideal plaza. A natural selection, whereupon cities develop and through time the failing are removed and the successful remain.

_PRESENT

Sitte believed that the approach of the then current town planners was a problem. To him the key shift in modern city planning was from an Artistic led ideology to that of a Service led, technocratic thought of mind. A city designed for machines, not for human beings.

The grid represented a critical failure in town planning. Sitte thought that the use of a grid led to inefficiency and hierarchically placed a critical element of town planning at the bottom of the list, public open space. The ‘grid’ is a service orientated approach. It concentrates on plumbing, hygiene, and the vehicle as the important elements, the public are seen more of a secondary if not tertiary component of the city. The ‘grid’ behaves in plan, but not section. It does not deal too well with difficult topography and land formation. The result leads to unused, unwanted space in the city that is normally deemed as suitable public open space. This idea frustrated Sitte, where the open space does not derive from anything, other than the offcuts, those irregular elements inappropriate for the built form. The open spaces should be around the activity, as in medieval squares, next to public buildings / markets / theatres. People flock to activity, the ‘grid’ eliminates activity.

Artistic principles were missing. It is those principles that generate a greater experience for the pedestrian and lead to the success of open spaces within cities. Sitte saw that the life of the common people has, for centuries, been steadily withdrawing from public squares, especially so in recent times. The lack of art acted as a catalyst for the transformation of the city into a machine.

Sitte saw the importance of the relationship between class and the public space. He outlined that the wealthy will always have other experiences driven by economy, the theatre and concerts for example, regardless of open space. Whereas the lower classes are affected significantly by those open spaces, ungoverned by their wealth. It is the parceling of plots, purely for economical considerations, that has become a problem in modern society and city planning. Sitte believed that the participation of art above all else affected those within a space.

_SOLUTION

Camillo Sitte concludes the book with his methods put into practice. Using the backdrop of his home city of Vienna, he adapts several existing spaces within the city to correspond to his beliefs. The Votive Church in Vienna sits isolated on it’s own, a characteristic deemed unsuccessful. He chooses to populate the plaza that envelops this extraordinary building. The building looks to create a series of smaller openings, looking to emphasise specific façades of the grand church, and concluding by manifesting itself into a comfortable experience for those that visit.

His ‘Artistic Principles’ do not take that of a rudimentary lateral form. There is no list of rules to follow, on the contrary, Sitte’s book, for all of it’s accounts of modern problems, is rather chivalrous to the current state. For all the magnitude his practice today has become, he study was one of modesty. His work is that of the ‘Human Condition’, it utlises the terminology and practice of what we know perceive as Town Planning, to improve the urban form in which he lived. Using the backdrop of his home city of Vienna, he adapts several existing spaces within the city to correspond to his beliefs. The Votive Church in Vienna sits isolated on its own, a characteristic deemed unsuccessful. He chooses to populate the plaza that envelops this extraordinary building. The building looks to create a series of smaller openings, looking to emphasise specific façades of the grand church, and concluding by manifesting itself into a comfortable experience for those that visit.

His ‘Artistic Principles’ do not take that of a rudimentary lateral form. There is no list of rules to follow, on the contrary, Sitte’s book, for all of its accounts of modern problems, is rather chivalrous to the current state. For all the magnitude his practice today has become, the study was one of modesty. His work is that of the ‘Human Condition’, it utlises the terminology and practice of what we now perceive as Town Planning, to improve the urban form in which he lived.

Thursday, 7 January 2010

Camillo Sitte (1843-1903): City Building According to Artistic Principles

First published as Der Städtebau nach seinen künstlerischen Grundsätzen in 1889

A précis by Rabaz Khoshnaw

Sitte’s book “City Building According to Artistic Principles” established basic principles of urban design. He strongly criticized the modern city planning that valued logic and mathematical solutions over artistic considerations. He considered contemporary gridiron subdivisions as monotonous and leading to the maximizing of land exploitation. He considered the proportions of town squares, monuments, and churches. Planning should be a creative art and the interplay between public buildings and open spaces was paramount to good planning.

The relationship between buildings, monuments and their plazas

Sitte emphasized that the centre of plazas must remain permanently vacant, simply because of the desire to leave the line of vision free and not blocked by monuments. Otherwise, in his opinion, not only would such monuments interfere with the view of buildings but the buildings would present the worst type of background for the monuments.

He also criticized the way of building churches or public buildings in the centre of the plazas, because they spoiled the view of the plaza and there would be no adequate space distance to see the façade of the building very well. Simply he called this as representing a lack of judgment.

Proportional relationship between the buildings façade and the dimensions of the squares

In a very large square the mutual relationship between the plaza and its surrounding buildings dissolves completely, and they hardly impress one as a city plaza. However, he admitted that this kind of proper relation is a very uncertain matter, since every thing appears on the subjective viewpoint and not at all on how the plaza appears in plan, a point which is often overlooked.

The size and shape of plazas

According to Sitte’s classification there are two categories of city squares, the deep type and wide type, and to know whether a plaza is deep or wide the observer needs to stand opposite the major building that dominates the whole lay out.

Thus Piazza S.Croce in Florence should be regarded as a deep plaza since all of it is components are designed according to their relationship to the main façade. So the classification is not about dimensions but is dependent on the relationship between the plaza and its surroundings.

Streets and visual succession

Streets in old cities have grown through the gradual development of the main routes of communication leading from countryside to their organic centres, therefore avoiding an infinite perspective view by the frequent displacing of the axis.

An examples for this is the Rue des Pierres in Bruges leading from the Grand Place to the cathedral of Saint-Sauveur. There is nothing of the uniformity of modern streets and all the façades pass in succession before the eye. Another example is Breite Strasse at Lubeck where a steeple dominates the entire street. For the pedestrians walking along the street the steeple is brought out at one moment. Afterwards it disappears again and the structure of the church never dominates the view because of the curving street path.

It is necessary to emphasize that straight streets cannot offer such scenery. Therefore the lack of this kind of charming route and visual succession is one of the reasons which has lead to the lack of picturesque effects in our modern urban plans.

Modern cities

In Sitte’s view the main problem of contemporary planning was the ignoring of aesthetic values and the absence of concern with city planning as an art. It was increasingly treated as only a technical problem with the straight lines and right angles of the gridiron characterising cities, and therefore urban life. For example the modern boulevard, often miles long, seems boring even in the most beautiful surroundings, simply because it is unnatural.

In contemporary city planning Sitte states that there are three major methods. They are the gridiron system, the radial system, and the triangular system. Artistically speaking not one of them is of any interest, for in their veins pulses not a single drop of artistic blood. A network of streets always serves only the purposes of communication, never of art, while the demands of art do not necessarily run contrary to the dictates of modern living (traffic, hygiene, etc.).

Plazas in the modern system

What artistic value is there in an open plaza when it is congested with foliage? So, as one of the basic principles of design trees should not be an obstruction to the line of sight. Sitte criticized the modern public garden which was surrounded by open streets. It was exposed to wind and weather and was coated with street dust. Formerly there were private gardens that belonged to palaces and were secluded from traffic, and such gardens fulfilled their hygienic purpose despite their small size. Thus all these open modern parks failed completely in their hygienic purpose and the fundamental reason for this was the block system of planning.

The relationship between the built-up and open spaces is exactly reversed. Formerly the empty spaces (streets and plazas) had an entity and impact. In the contemporary planning process of laying out buildings the left-over irregular wedges of plots often become plazas!

Artistic limitation of modern city planning

Sitte’s analysis developed in response to the following contextual factors. Commercial activity had increasingly abandoned public open space. Public affairs were discussed in the daily paper instead of plaza. Economic growth led to the regular parcelling of lots based on purely economic consideration. Works of art were straying increasingly from streets and plazas into the art cages of the museums. And above all the enormous size to which the larger cities grew led to a consequent inflation in the size of streets and squares.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)